After a decade of VC influence at Stanford, what’s next?

- ParlayMe

- Apr 27, 2021

- 15 min read

Author: Abbey Goldberg

Editor’s Note: This piece was written in partnership with the Stanford Tech History Project, which seeks to document how Stanford’s tech ecosystem has changed since 2010. The full report will be published on Monday, April 26th. click here.

This portion of the Tech History Project aims to document how Stanford’s ties with venture capital have changed over the past decade, as well as make recommendations for improving them going forward.

Interestingly, and more broadly, this section aims to write a history of something whose main thrust is oriented toward the future.

Venture capitalists are a primary source of vigor for the entrepreneurial ecosystem of Silicon Valley, and venture capital as an asset class largely punches above its weight. Since 1974, over 40% of U.S. company IPOs have been venture-backed, and over the past three decades venture capital has become a dominant force in the financing of American companies like Apple, Google, and Microsoft. In fact, venture capital has generated more economic and employment growth in the United States than any other investment sector; annually, venture investment makes up only about 0.2% of GDP, but delivers more than 20% of U.S. GDP in the form of VC-backed business revenues.

A primer on venture capital

“By financing startups, venture capitalists accumulate entrepreneurial knowledge. They are the memory of the complex network of the Silicon Valley.”

— Michel Ferrary and Mark Granovetter, authors of The Role of Venture Capital Firms in Silicon Valley’s Complex Innovation Network

Before going further, it will be beneficial to provide a working definition of venture capital and take a preliminary look at the activities of venture capitalists. The abbreviation “VC” may be used to refer to both the venture capital industry as a whole, as well as an individual venture capitalist.

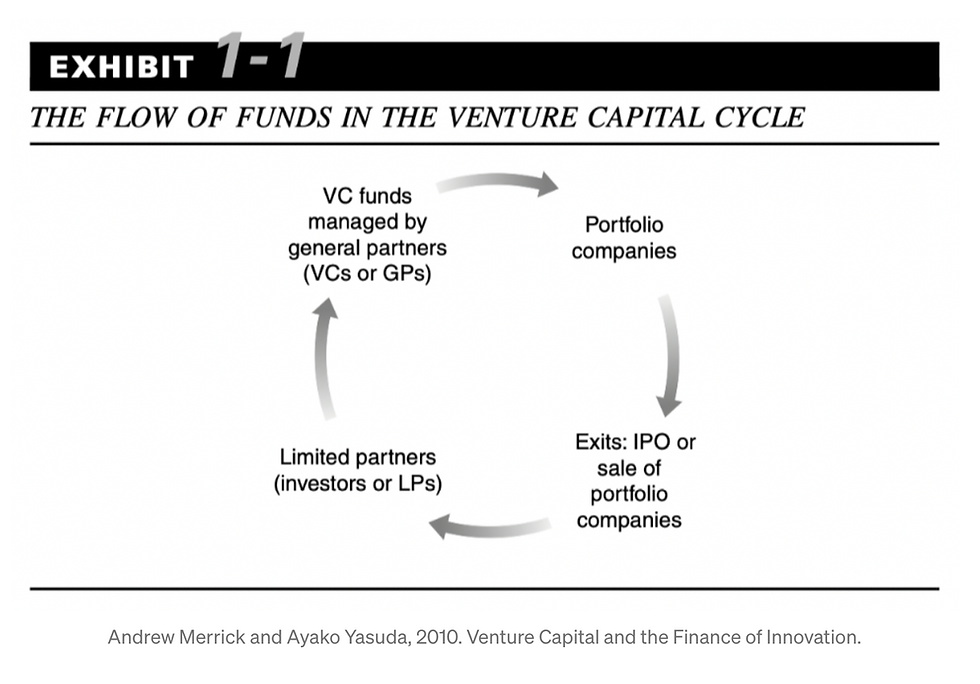

A VC has five main characteristics, according to a seminal book on the topic:

A VC is a financial intermediary, taking capital from investors (or “limited partners”) and investing it directly into early-stage companies.

A VC invests in private companies.

A VC takes an active role in helping the companies in its portfolio.

A VC’s primary goal is to maximize its financial return by exiting investments, either through a sale or an initial public offering (IPO).

A VC invests to fund the internal growth of companies.

Andrew Merrick and Ayako Yasuda, 2010. Venture Capital and the Finance of Innovation.Another definition that will be helpful here is that of an angel investor. Angel investors are similar to VCs in some ways, but different primarily in the fact that angels use their own capital (thus not satisfying characteristic (1) outlined above). Venture capital in Silicon Valley

Why Silicon Valley?

Silicon Valley is characterized by high clustering density, where “ethnic ties, university ties, friendship ties, past professional ties and current professional ties are intertwined” to sustain innovation and entrepreneurship.

Historically, Silicon Valley is characterized by a meteoric rate of startup creation — Hewlett Packard, Intel, Oracle, PayPal, Instagram, and Google (just to name a few) were all founded in Silicon Valley. A majority of the aforementioned companies were created by Stanford students or alumni.

Perhaps one of the biggest factors here is Stanford’s proximity to Sand Hill Road, a 5.6-mile arterial road in Silicon Valley notable for its concentration of venture capital firms. Considered the “Wall Street of the West Coast,” Sand Hill Road has been the connector between ambitious founders and funding partners for decades.

Some of the venture funds on Sand Hill Road (Bloomberg).Venture capital firms play a prominent role in Silicon Valley’s complex innovation landscape. In particular, these venture funds participate in a reflexive interchange of startup and VC knowledge, one that has enabled Stanford University and the broader Silicon Valley ecosystem to both benefit mutualistically from one another. The following sections will go into more detail on the roles that these players both contribute to the ecosystem.

“These institutions continue to provide a diverse and highly talented executive and technical workforce. But they do more than teach students… It’s a mistake to see this traffic in knowledge as a one-way street. These excellent schools feed the firms of the Valley… But as I note below, the firms in the Valley also help feed the excellence of the schools” —

Martin Kenney, author of Understanding Silicon Valley: The Anatomy of an Entrepreneurial Region

Venture capital within Stanford’s ecosystem

Given its central role in Silicon Valley, Stanford has been one of the most successful universities in the world for creating companies and attracting funding. Unsurprisingly, the past decade’s fundraising data is consistent with this trend. More often than not, Stanford has been at the top of the list of universities producing the most VC-backed entrepreneurs, and during this period, there has been a substantial increase in funding received by Stanford-affiliated startups.

“Venture capitalists routinely back more founders coming out of the Stanford business program than any other university in the country.”

Compiling raw data from several PitchBook university reports, we found that in the first half of the decade (January 2010 to July 2015), Stanford produced 955 company founders, who created 813 companies and raised $10 billion. By contrast, in the second half of the decade (August 2016 to September 2020), there were 798 new founders and 741 new companies, with the total funding reaching $54.1 billion, a 540% increase from the amount raised in the decade’s first half (Source 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

(NOTE: PitchBook was much more poorly populated in the earliest years of the past decade, and the extraordinary increase in venture capital funding is partly attributable to the availability of better data metrics (not necessarily a real increase). We employed the statistical technique “difference in differences” to assess whether the unusual surge in funding was seen in other universities as well, and the results confirmed our suspicion: Harvard had a 704% increase, MIT had 262%, and UPenn had 408%. As such, it’s likely that Stanford’s increase was overstated, and it would be misleading to present these results without this caveat. Because very few companies release reports on university entrepreneurship, PitchBook’s reports are still the most comprehensive and widely cited. As such, we decided to include this data in our report, and we believe it does capture the overall direction of movement around VC funding.)

Funding raised by Stanford founders in the last decade, according to PitchBook. Please do not interpret this data without reading the important caveat noted above.While Stanford topped the rankings of undergraduate programs producing most entrepreneurs, in the graduate programs list, Harvard Business School remained ahead of Stanford Graduate School of Business throughout the decade. One explanation for the business school gap could be the bigger size of Harvard’s MBA classes, which is almost 2.5 times that of GSB’s.

The remarkable rise in funding for Stanford startups has been fueled by a combination of catalysts, including both macro trends and Stanford-specific advantages. We discuss some of the Stanford-specific advantages — like classes, clubs, and scout programs — later in this section, but two industry-wide macro trends include:

The advent of the Web 2.0 revolution, as articulated in Marc Andreessen’s prescient op-ed “Software is eating the world.” In the past decade, software-based solutions supplanted products and services traditionally delivered through other means. Stanford students and alumni were at the forefront of this disruption, founding startups like SoFi, StubHub, Robinhood, and Instagram.

An unparalleled rise in global venture capital financing, coinciding with a drop in the number of funded startups.

Invested capital, compared with number of deals, over the last decade globallyOf course, Stanford also has a variety of its own specific advantages that help to explain the impressive rise in funding for Stanford startups over the past few decades. As Contrary Capital put in its inaugural university rankings:

“If you’re a university entrepreneur, it’s tough to beat Stanford. It has it all: perhaps the best strategic location out of any university with Sand Hill Road on its doorstep, top-tier programs in nearly every field, and a decades-long entrepreneurial culture. Underappreciated in impact is Stanford’s leave of absence policy — students can leave for a full year without consequence. This dovetails well with their flexible curricula. Pairing access to high-quality resources with the freedom to work on anything predictably spawns interesting companies every year.”

In addition, some particular aspects that also play a role include Stanford’s classes, organizations, campus accelerators, student-run venture funds, and venture capital scout programs. We go into more detail in the sections below.

Classes

“[Stanford’s] campus, in fact, seems designed to nurture such success. The founder of Sierra Ventures, Peter C. Wendell, has been teaching Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital part time at the business school for twenty-one years, and he invites sixteen venture capitalists to visit and work with his students. Eric Schmidt, the chairman of Google, joins him for a third of the classes, and Raymond Nasr, a prominent communications and public-relations executive in the Valley, attends them all. Scott Cook, who co-founded Intuit, drops by to talk to Wendell’s class. After class, faculty, students, and guests often pick up lattes at Starbucks or cafeteria snacks and make their way to outdoor tables.”

— Ken Auletta, The New Yorker (2012)

The past decade has seen a major influx of venture capital and startup-related courses on Stanford’s campus.

Lean Launchpad, one of Stanford’s flagship entrepreneurship classes, was founded in 2010. (This class is discussed in more detail in the External Relationships section of this report.) Not long thereafter came CS 183 (aptly named “Startup”) taught by venture capitalist Peter Thiel ’89 JD ’92. Shortly after that came Startup Garage in 2013, and Sam Altman’s “How to Start a Startup” in 2014. Other popular classes from the last decade include Technology-Enabled Blitzscaling with Reid Hoffman ’90; Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital with Peter Wendell, Andy Rachleff MBA ’84, and Eric Schmidt; and Technology Entrepreneurship with Tom Byers. Today, according to our survey, over 50% of students “in tech” (and 38% of students in general) have taken an entrepreneurship class by their senior year.

Note: A more robust list of entrepreneurship-related courses can be found on the Stanford Technology Ventures Program website.

Clubs & Organizations

Outside of classes alone, Stanford’s campus is home to a host of venture capital-related clubs and organizations. Among undergraduates, the Business Association of Stanford Entrepreneurial Students (BASES), a Stanford-sponsored student organization, is popular and highly regarded. Along with hosting frequent chats with entrepreneurs, BASES runs the Startup Career Fair with BEAM, the official campus career center, and coordinates the annual Startup Challenge competition with a total of $100,000 in prize money. In a similar vein, ASES, a Stanford-based global entrepreneurship group, hosts VC3, a daylong event that brings together VC firms from Silicon Valley and Stanford-affiliated startups for rotating pitch sessions.

BASES Startup Challenge in 2014. Credit: Akiharu Maki (Source).A more tight-knit community on campus in this realm is Stanford Venture Capital Club (SVCC), founded in 2012. The club is comprised of a well-connected group of students working in and around venture capital. SVCC members work intimately with a handful of venture firms in Silicon Valley to conduct market research and work on various projects. Many have gone on to become investors themselves, with SVCC alumni at top venture firms including Sequoia, Founders Fund, Bessemer, CRV, and more.

Among graduate students, the GSB Entrepreneurship Club, or E-Club, is particularly popular. One of the oldest student-run entrepreneurial clubs in the nation, the organization hosts one of the largest annual conferences dedicated to entrepreneurship in the world. Today, the Entrepreneurship Club claims to be the most active student-run club within the Graduate School of Business community.

Campus Accelerators

Stanford also provides its own host of accelerator programs, which serve not just as funding sources but also as mentorship opportunities for early-stage startup founders.

StartX

One of Stanford’s most successful accelerators is StartX, a non-profit educational accelerator and founder community for Stanford affiliates run by a number of entrepreneurs and Stanford professors. StartX was founded in 2009 and developed through $7M+ in grant funding from Stanford University and Stanford Health Care to support the university’s entrepreneurship ecosystem. (Today, StartX operates independently from the university.) StartX’s alumni include companies like Lime, Patreon, and Branch, to name a few; after ten years of activity, the combined market cap of StartX’s alumni is $25B+ with more than 80 acquisitions. According to a report in The Stanford Daily in 2019, “StartX has now guided 650 companies, 83 percent of which are growing or have been acquired… In a testament to its growth, StartX says its companies now raise $9.3 million on average, many times the $1.1 million its companies raised on average half a decade ago.”

Source: StartXLaunchpad

Once referred to by Forbes as an “entrepreneurship factory,” Launchpad is an intensive ten-week program designed for Stanford students who are primed to prototype and sell business ideas. Founded in 2010, Launchpad runs on campus each spring and is taught by d.school adjunct professors Perry Klebahn and Jeremy Utley. Since its inception, Launchpad has helped Stanford-founded startups raise over $500 million in venture capital funding. Today, 60% of Launchpad ventures are still in business.

Stanford Venture Studio

The Stanford Venture Studio is an entrepreneurship hub for graduate students exploring new venture ideas. It connects students to resources, entrepreneurial expertise, and an interdisciplinary community of like-minded peers and alumni. Over a hundred teams work in the Venture Studio each year; the studio is not selective and offers year-round enrollment to graduate students from any Stanford school.

Alchemist Accelerator

In 2012, Stanford lecturer Ravi Belani founded Alchemist Accelerator, a venture-backed accelerator focused on accelerating the development of “seed-stage ventures that monetize from enterprises.” In 2016, CB Insights rated Alchemist the top accelerator based on median funding rates of its graduates (Y Combinator held the #2 slot). The accelerator’s portfolio includes companies like MobileSpan, a Stanford-founded startup acquired by Dropbox in 2014. Since its formation, 34 of its accelerated companies have been acquired.

Cardinal Ventures

Another accelerator, and perhaps most familiar to Stanford students, is Cardinal Ventures, the equity-free startup accelerator run exclusively by and for students under Stanford Student Enterprises (SSE). Over the past five years, Cardinal Ventures has graduated over 90 companies, going on to cumulatively raise more than $366 million from venture funds like Sequoia, Y Combinator, Initialized, and Kleiner Perkins.

Y Combinator

Although not a campus-specific accelerator, we would be remiss not to reference Y Combinator, the powerhouse startup accelerator founded in 2005 by Paul Graham, Jessica Livingston, Trevor Blackwell, and Robert Tappan Morris. Originally, Y Combinator held two programs: one in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and one in Mountain View, California. In 2009, however, they announced that the Cambridge program would be closed and all future programs would take place in Silicon Valley. Y Combinator’s success coupled with this decisive move to the Silicon Valley ecosystem helped spur a series of new accelerator and incubator programs (like the ones mentioned above, among others). Access to such institutions has made — and continues to make — a significant difference in the fundraising prospects of Stanford founders and startups.

Student-run Venture Funds

The past decade has also seen the rise of student-run and student-owned VCs. Venture funds like Dorm Room Fund (founded in 2012 and backed by venture firm First Round) and Rough Draft Ventures (founded in 2012 and backed by venture firm General Catalyst) can also be found on Stanford’s campus, with a handful of both undergraduate and graduate students on the funds’ San Francisco investment teams.

Contrary Capital, another university-focused venture fund with a nationwide network of over 100 student venture partners across more than 50 universities, also has a presence at Stanford. Contrary’s portfolio includes DoorDash, which was founded in 2013 by four Stanford students.

On top of this, in 2010, Stanford University alumni and venture capitalists Miriam Rivera and Clint Korver founded Stanford Angels & Entrepreneurs (SA&E), which seeks to strengthen Stanford’s startup community by fostering relationships among entrepreneurs and alumni investors. Membership is open to all Stanford alumni and affiliates, including students, faculty, staff, and parents or spouses of alumni or students. To date, Stanford Angels & Entrepreneurs has helped fund over 40 startups.

And if this were not yet enough, last year welcomed the birth of the Stanford 2020 Fund, a new venture fund created entirely by Stanford business school classmates to invest in their fellow students’ ventures. As of July 2020, they have already raised $1.5 million across 175 investors for the new fund, with 50 investors willing to give $500,000 on the waitlist. The group plans to invest between $50,000 and $100,000 in Stanford-founded startups depending on round size and valuation.

Venture Capital Scout Programs

Lastly, a striking trend within the broader Silicon Valley entrepreneurial network is the rise of venture capital scout programs, where “scouts” — generally well-networked individuals — are empowered to invest money in startups (usually in ~$50k increments at the pre-seed and seed stages, the earliest stages of a company’s lifecycle) on behalf of a venture capital fund. Sequoia Capital is commonly credited with inventing the scout program in 2009; since then, the practice of employing scout programs has blossomed among legacy firms, who now deploy billion-dollar funds but still want to remain competitive with smaller investments at the seed stage.

Of course, this trend of venture capital scout programs has naturally extended into Stanford’s university ecosystem. On Stanford’s campus specifically, scouts can be found from Sequoia, Lightspeed, Pear VC, and more.

(Note: The list goes beyond what we can cover in this report. Other venture firms using such programs are Accel Partners, CRV, Founders Fund, Index Ventures, Social Capital, and Spark Capital, according to the Wall Street Journal.)

Pear VC’s program has a particularly strong impact on Stanford’s campus. Founded in 2014, Pear VC invests in startups spanning three stages of company development: pre-seed, seed, and Series A. Over the past six years, Pear’s portfolio has had two IPOs (Guardant Health and DoorDash), along with $5 billion in total capital raised. Pear has a strong belief in student founders: nearly 50% of their portfolio companies were founded by students. Of particular relevance here is Pear Dorm, their program specifically designed to provide entrepreneurial support to students and recent graduates. Coupled with this is their Pear Fellows program, which provides a VC apprenticeship for students interested in developing their venture capital knowledge and reputation. The program is limited to five campuses: Stanford, U.C. Berkeley, Harvard, MIT, and Penn. As such, Stanford students (both undergraduate and graduate) have historically found myriad ways to be involved with Pear VC while still enrolled full-time.

An Outlook for the Future

“[Stanford is] the germplasm for innovation. I can’t imagine Silicon Valley without Stanford University.”

Stanford and VC are inextricably linked, given many of the major venture capital successes have come out of Stanford. In many ways, Stanford had a vital role in creating the Silicon Valley-style of venture capital we know today.

As we’ve seen, this symbiosis has become more tightly coupled over time as venture capitalists want increased access to the next generation of great founders. This has happened both from the VC side (Sequoia’s creation of the scout program, Pear VC’s reach on campus, etc.) as well as the university side (Startup Garage, Stanford Venture Capital Club, and other venture-related organizations).

At times, this coupling may go too far. For example, it’s not uncommon for Stanford professors to invest in their students’ companies — in 2013, a company named Clinkle made news for this reason. The company was funded in part by university professors, and Stanford’s then-president John Hennssey had served as the academic adviser to Clinkle’s CEO while was an undergraduate. Situations like this raise “complicated questions about values and conflicts: Do students get good grades if they start a company that their professors invest in? Professors have coercive power, which isn’t the best thing to pair with financial opportunity.”

In 2012, a widely-discussed article titled “Get Rich U” summarized the overarching concern succinctly: “There are no walls between Stanford and Silicon Valley. Should there be?” How will these trends evolve over the next decade? Perhaps we will see even tighter coupling between Stanford and Silicon Valley’s mutualistic relationship. Or, tangentially, maybe these trends will expand beyond just computer science and engineering: what would a “Startup Garage” in, say, the biology or robotics departments look like? Startup culture has slowly begun to trickle into other domains; for example, hackathons, historically hosted by tech companies/organizations and targeted towards software engineers, are now becoming more prevalent in other verticals. The Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research is known for hosting “policy hackathons” on campus, like a hackathon for criminal justice reform in partnership with Stanford in Government. We anticipate that this trend will continue. We also optimistically anticipate an increase in diverse founders and funders within Stanford and Silicon Valley’s respective ecosystems. In today’s bull market, venture capital is incredibly competitive. There are a large number of emerging funds sharing space (and competing for investment allocation) with larger, more institutional funds. Additionally, last year’s expanded accredited investor definition has further increased the pool of eligible investors for early-stage companies. Over the next decade, these trends will only intensify. As venture capital becomes increasingly accessible to founders, it will naturally have to expand to meet founders’ needs — that is, to include more diverse voices, backgrounds, and perspectives. In particular, scout programs play an important role here. Serial entrepreneur and angel investor Jason Calacanis agrees: “They’ll never get enough credit for this, but one thing Sequoia did was use scouts to radically increase the amount of diversity in the industry… They opened the aperture to get more women and underrepresented investors [into their network].”

Of course, there’s still a long road ahead. Only 9% of investment decision-makers in VC today are women; just 2% are Black. If the venture capital industry reached a wider group of investors, the economy would be better off. A more diverse venture ecosystem would help spread the wealth of economic growth to more people. With Stanford — and Silicon Valley as a whole — at the forefront of venture capital innovation, it is well-positioned to help accelerate these changes. As mentioned above, this is directly applicable to scout programs, which are becoming increasingly common: these programs should be composed of a diverse set of people, and unique backgrounds & perspectives should be viewed as a strategic advantage. But this recommendation can also be applied more broadly. Innovation is everywhere, so access to capital should be, too. Anywhere venture capital touches Stanford’s ecosystem — from classes to clubs to on-campus accelerators — the example should be set that diversity of thought, backgrounds, and experiences is a net positive for everyone. Working to make these changes will ensure that Stanford continues to raise the bar and set an example as one of the most successful universities in the world for innovation.

Thank you to my classmate and Stanford Tech History Project Director Nik Marda for inviting me to join this initiative, and thank you to my friends John Luttig, Josh Payne, and Midas Kwant for the feedback and comments!

Article originally published on Medium

About the Author:

Gaby Goldberg

Investing @BessemerVP & studying Symbolic Systems @Stanford. Previously @ChapterOne. Follow me @gaby_goldberg.

Comments